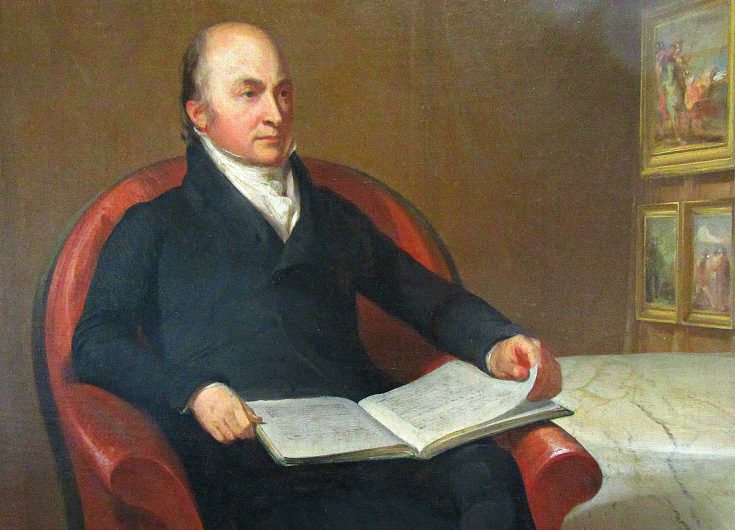

JQA, Chronicles of an American Diplomat: Dispatch 9

While waiting for the decision by the States General on his status, John Quincy received a letter from the Amsterdam Bankers. It was bad news: The Bankers had done nothing on the loan of 800,000 dollars, lacking the notice of commission that David Humphreys, the American minister in Lisbon, was supposed to send them. They added that under the present circumstances the loan would be altogether impracticable, and they could not foresee a time when it might again be feasible. John Quincy sent this information to the US Secretary of State, assuming that he and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton had already been made aware of this.