John C. Calhoun, Report on the Reduction of the Army (1820)

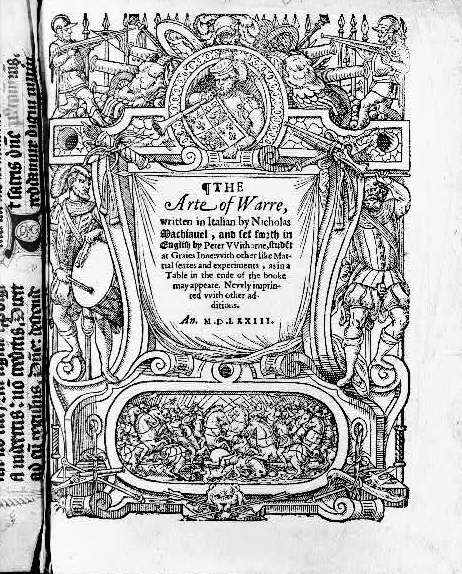

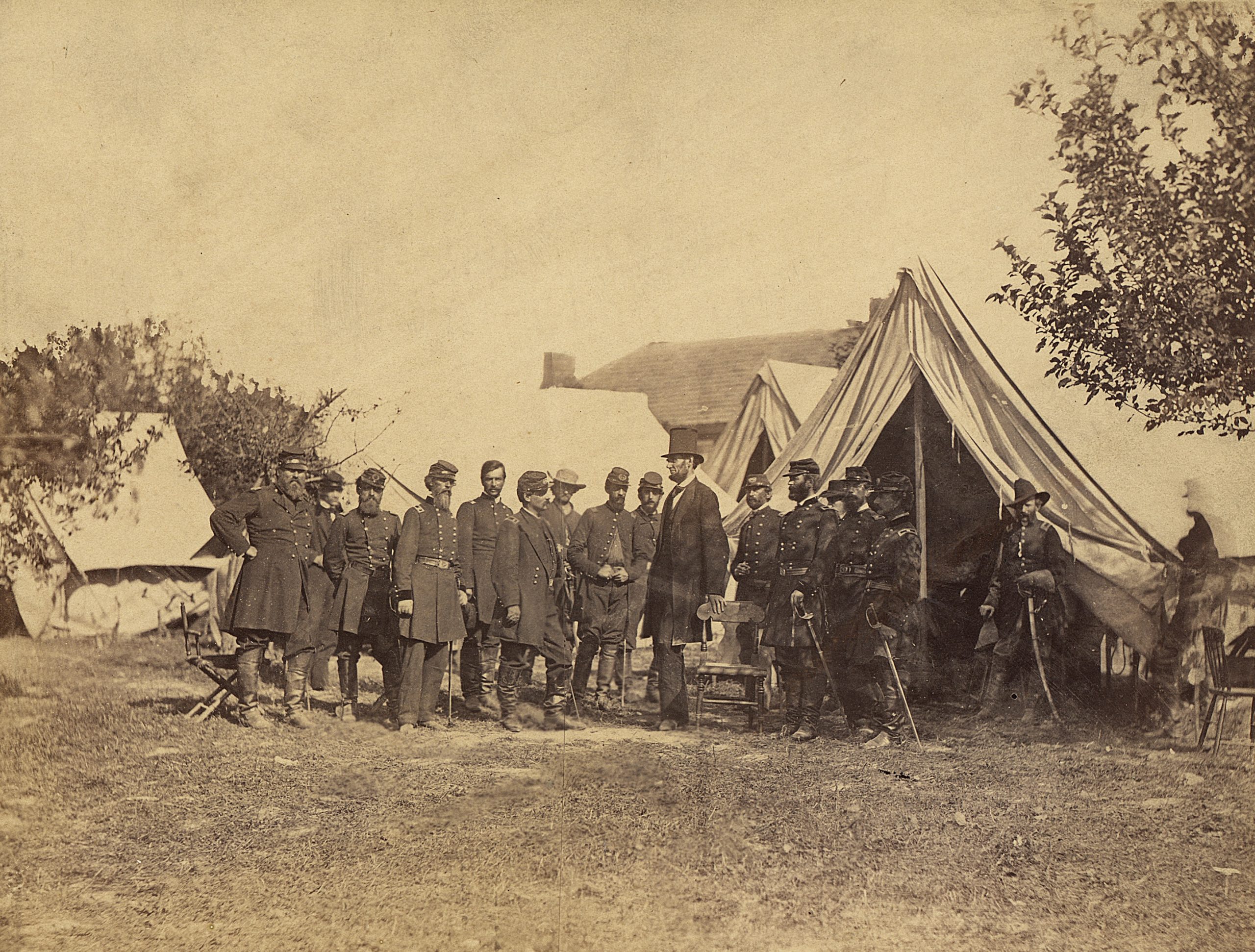

John C. Calhoun has gone down in American history as the great theorist of state rights, with the associated doctrines of nullification and the concurrent majority, qualifying him as the intellectual grandfather of secession and the Confederacy. But in his early public career, Calhoun was a staunch nationalist, a supporter of the War of 1812, and one of the Republic’s most distinguished Secretaries of War. Among his significant contributions to American statecraft was a Report on the Reduction of the Army, dated December 12, 1820.