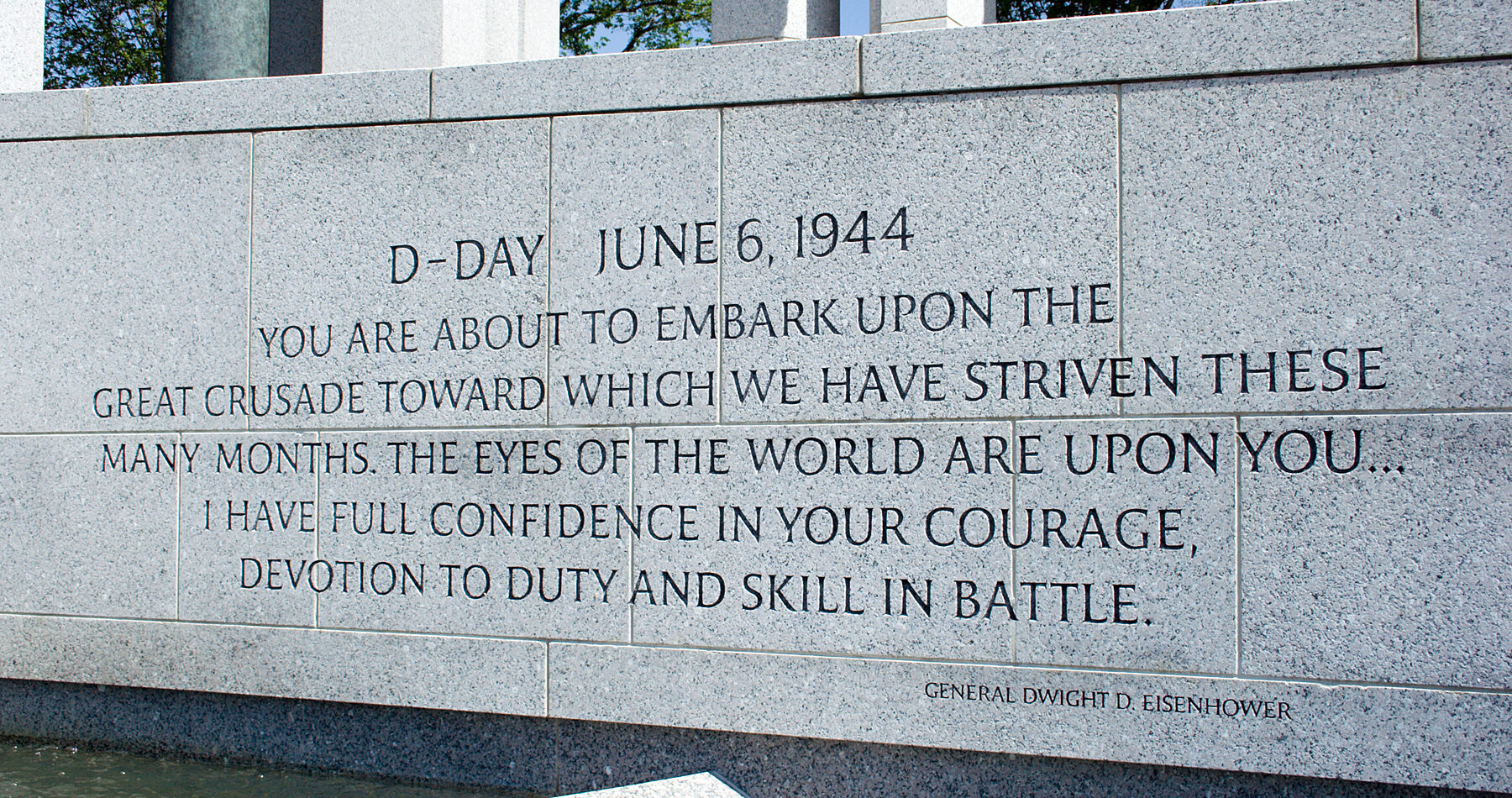

George Washington’s Farewell Address holds a revered, even sacred, position in the tradition of American foreign policy since its publication in 1796. The Senate reads it aloud annually on Washington’s birthday. Statesmen and policy makers excoriate each other for departing from its wisdom about the national interest. Only Andrew Jackson saw fit to join Washington in offering a farewell address at the end of his presidential tenure, until Harry Truman initiated the tradition for every subsequent president to offer such a speech. While the nation’s first president set the standard for all such addresses, only Dwight Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address, later known as the “Military-Industrial Complex Speech,” approaches Washington’s Address in influence and honor.

Eisenhower delivered his Farewell Address under circumstances quite different from Washington’s. While Washington famously urges America to focus on preserving union at home for the “permanency of [its] felicity as a people,” Eisenhower identifies extensive foreign involvement as a necessity to preserve peace and “enhance liberty, dignity, and integrity among people and among nations.” These two presidents seem to offer very different visions of the basic purposes of American foreign policy. Can the principles of the two speeches admit reconciliation?

Washington and Eisenhower, alike statesmen and generals, perceive the dangers of using military arms and alliances without circumspection. But the two men also indicate that categorical imperatives do not befit statecraft. Both believe the American Union to be sacred and its preservation the primary purpose of American foreign policy. Each recognizes in his own way that preservation of the Union at home could require American action abroad. Key for both presidents is the exercise of circumspection, the part of prudence that judges the suitability of available means in present circumstances.[1] The American statesman must be circumspect about the nature of international relations, but also about the character of his own regime. The Farewell Addresses of Washington and Eisenhower exemplify this circumspection and disclose the necessity of good judgment for applying political principles to changing circumstances.

Isolationism and Washington’s Teaching on Duty to One’s Own

Washington’s Farewell Address opens with the observation that America’s “perplexed and critical” international situation had compelled him to remain in office.[2] Seen in this light, foreign relations seem to be merely a distraction from domestic political life. To the extent that foreign policy has any value, it is only insofar as it promotes national security and respectability. Washington reiterates what he had emphasized in his First Annual Message to Congress, that an American’s sacred duty is to the Union. Correlating with this domestic duty is Washington’s “great rule of conduct” regarding foreign nations: “in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.” Foreign affairs seem to offer only dangers; blessings are found at home.

Given America’s uncertain international circumstances during Washington’s presidency, it is not surprising that he emphasizes the ways in which foreign entanglements could wreck the young republic. Washington, Adams, and Jefferson would likely concur with Alexis de Tocqueville’s assessment that democracies are generally outclassed in foreign policy.[3] On the basis of this view, Washington’s Farewell Address seems to establish the orthodox opinion that America must keep to its own. Interpreted in this way, the Address (and later the Monroe Doctrine) seems to support the kind of isolationism typical of many ordinary Americans as late as the Cold War.[4] Yet this “myth of virtuous isolation” depends on a “peculiarly literal-minded and unhelpful simplification of a complex tradition.”[5] Isolationists tend to abstract passages of Washington’s Farewell Address from their textual and historical context for the sake of supporting the “one true faith.” The Address itself simply does not support a categorical imperative for the United States to isolate itself from foreign affairs.

Washington’s precise argument is that any relations with foreign powers must serve the national interest of the United States. He intends for this policy of detachment from foreign entanglements to change “when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel.” This passage from the Address is reminiscent of Hamilton’s argument from Federalist No. 11.[6] There, Hamilton portrays America as a rising competitor to Europe. America’s “adventurous” commercial spirit will (and he implies, should) make the European maritime powers uneasy. Prefiguring passages from the Farewell Address, which Hamilton assisted Washington in drafting, Hamilton argues,

There can be no doubt, that the continuance of the union, under an efficient government would put it in our power, at a period not very distant, to create a navy, which, if it could not vie with those of the great maritime, would at least be of respectable weight, if thrown into the scale of either of two contending parties… A few ships of the line, sent opportunely to the reinforcement of either side, would often be sufficient to decide the fate of a campaign, on the event of which, interests of the greatest magnitude were suspended. Our position is, in this respect, a very commanding one.[7]

Necessities of circumstance and regime require America to develop a military that can protect its commercial interests. As those interests expand, military strength must increase, until America is capable of dictating “the terms of connexion [sic] between the old and the new world.”[8] Even prior to the Monroe Doctrine, Washington and Hamilton deem it likely that American commerce would soon necessitate extended involvement in foreign affairs.

To be sure, Washington speaks more reservedly in his Farewell Address than Hamilton does in The Federalist Papers about the implications of expanding American commercial power. Washington’s express wariness about foreign involvement seems to be a countermeasure against premature American involvement. In his book on the drafting of Washington’s Farewell Address, Felix Gilbert observes that,

Ideas which in the Address were only vaguely adumbrated were more clearly expressed in the eleventh number of the Federalist. In the Farewell Address, emphasis was laid on Europe’s possessing a special political system; the consequences of this point—that America had a political system of her own—was only suggested. The statement in the eleventh number of the Federalist that the United States ought “to aim at an ascendant in the system of American affairs” revealed Hamilton’s full thought. Because Washington hardly would have liked this open announcement of an aggressive imperialist program, Hamilton refrained from expressing this idea explicitly in the Farewell Address.

While Washington’s Farewell Address does not explicitly call for America to take on the kind of international leadership to which Hamilton aspires, it does not exclude that possibility. It certainly is no manifesto for isolationism, even if it does present a view of the international as a realm of danger and necessity.

Foreign Entanglements and Overgrown Military Establishments

If Washington agrees with Hamilton that American will become more involved in foreign affairs at a time “not far off,” why does he so emphatically reject political bonds with other nations? And why does he stress the danger of an overgrown military establishment? Arguably, these proscriptions against allies and arms are the most repeated lessons from Washington’s Farewell Address.[9] Yet Washington’s admonition to follow the American national interest, to maintain a policy of neutrality for now, and to set limits on the military establishment, is not incompatible with the foresight that the American republic would someday have a larger sphere of interest.

In an often-quoted passage of the Farewell Address, Washington writes: “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world, so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it….”[10] Washington’s chief concern is that weaker states lose sovereignty when they attach themselves to more powerful nations; surely Washington has in mind the one-sided nature of the “alliance” between England and each of its colonies.[11] Washington also is keenly aware of the unique problems that the French Revolutionary Wars had posed for America. The incidents involving Citizen Genêt—a French envoy whom Washington declared persona non grata for encouraging sedition against the American policy of neutrality—rightly had raised concerns in Philadelphia about foreign influence on American domestic politics. At the same time, Washington recognizes that British disregard for American neutrality would threaten to draw America into war against France. As president, he had therefore been compelled to navigate between two opposite extremes, either of which would mean American involvement in a Great Power conflict for which it was not prepared.

In this context, Washington’s advice against permanent alliances resonates less with 20th-century isolationism than with the realist dictum attributed to Lord Palmerstone that nations have no permanent friends or allies. The only enduring community of interests is found within one’s country, not among nations. Nations act for egoistic motives, and this self-interested character of international politics may require either neutrality or involvement as the circumspect statesman determines at a particular moment.[12]

In a speech delivered to the U.S. Senate in 1853, William H. Seward (Abraham Lincoln’s future Secretary of State) offers a prudential interpretation of Washington’s warning about “entangling alliances.”[13] Seward notes first that this policy of avoidance had been necessary for the young republic.[14] However, Seward does not rest his case merely on the historical situation. He points to Washington’s own clarification that the policy of neutrality derives “from the obligation which justice and humanity impose on every nation, in cases in which it is free to act, to maintain inviolate the relations of peace and amity toward other nations.” That is to say, the necessities of international politics constrain a nation’s choice of policy, but this does not mean that a nation should never have an active foreign policy. Seward further clarifies that Washington does not advise American statesmen to avoid all ties with other nations but only “artificial” ones, so judged according to “the natural course of things.” The norm for American foreign policy should be “liberal intercourse with all nations,” but America may still require alliances, despite the fractious character of even the best international ties.

Seward also emphasizes that Washington’s concerns about permanent alliances and political ties (a term Washington himself directed the printer to italicize[15]) derive from the principle that American foreign policy should follow the national commercial interest.[16] Washington agrees with Madison that politics should follow commerce, not the other way around.[17] Yet it should be kept in mind that this agreement about the primacy of commerce conduces to Hamilton’s conviction that expanding commerce would require extensive diplomatic ties and augmented military strength. America would need political connections in the future, but these connections should not be seen as permanent or as divorced from the national commercial interest.

Complimenting his warning about unnecessary political ties, Washington urges the United States to “avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.” Love of the Union furnishes the greatest security for America. Washington’s fear almost seems closer to the antifederalist position outlined in Brutus No. 8 than to Hamilton’s claim in Federalist No. 24, that concern about standing armies rests “on weak and unsubstantial foundations.”[18] Yet Washington gives no evidence of sharing the antifederalist conviction that a standing army necessarily leads to tyranny.[19] On the contrary, Washington perceives that wars are “unavoidable.” In his First Annual Message to Congress, Washington explicitly espouses the principle, si vis pacem para bellum: “To be prepared for War is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.”[20] It is therefore fitting that Washington also expresses this view in his final Message to Congress, mirroring an argument that Hamilton makes in Federalist No. 24:

To an active external Commerce, the protection of a Naval force is indispensable. This is manifest with regard to Wars in which a State is a party. But besides this, it is in our own experience, that the most sincere Neutrality is not a sufficient guard against the depredations of Nations at War. To secure respect to a Neutral Flag, requires a Naval force, organized, and ready to vindicate it, from insult or aggression.[21]

Quite unlike his (first) Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Washington is convinced that America requires a “moderate” navy.[22] He also urges the creation of a military academy to train officers for both naval and land forces—a request that calls to mind Washington’s frequent complaints during the War of Independence about the handicap of leading amateur soldiers against British regulars.

Washington’s awareness of the political dangers posed by a standing army does not imply an absolute denial that a large military could become necessary. He advises neutrality, but in his own initial draft of the Farewell Address, he writes that neutrality would be a strict necessity only “within the next twenty years,”[23] and he explicitly hopes that America “may be always prepared for War, but never unsheathe the sword except in self-defence [sic] so long as Justice and our essential rights, and national responsibility can be preserved without it….”[24] In short, his position on American military capability is neither minimalist nor maximalist. He counsels readiness for war, but most of all circumspection that balances the domestic political effects of a standing army against the ever-looming necessity of war among nations.

Turning to Eisenhower: The Cold War and the Duty to Lead

Like Washington, Eisenhower esteems “the national good” as a unifying purpose that surpasses “mere partisanship.” But Eisenhower’s Farewell Address expresses pride in “America’s leadership and prestige” abroad, and these qualities depend “on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.”[25] This duty to lead would seem to be completely opposed to the purely domestic sense of duty that Washington teaches. Eisenhower dares to extend America’s national good to include international peace, progress, and liberty. “To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people.” More than anything else in the two Farewell Addresses, Eisenhower’s apparent belief in the convergence of the national and the cosmopolitan conflicts with Washington’s exclusive concern for America’s own interest.

In truth, Eisenhower’s position is a reformulation of—not a radical departure from—Washington’s foreign policy principles. As previously discussed, Washington’s farewell warning about entangling “our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship [sic], interest, humor, or caprice,” stem from the conviction that “Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none or a very remote relation.” But what should America do if the growth of interests that Hamilton explicitly (and Washington tacitly) expects become conjoined, either by crisis (such as German expansionism) or by the gradual development of commercial ties? Eisenhower touts American international leadership as a source of benefit to all nations; yet he is convinced that this leadership is necessary primarily to defend American interests—and even to uphold the American way of life. It is true that he makes this case in terms of America’s “political faith,”[26] but the reasoning behind Eisenhower’s policies rests more on a calculation for the national interest than on idealistic hopes.

Like Washington, Eisenhower presents duty and necessity as the two guides of American foreign policy (a paradoxical combination, as will be discussed later on). Eisenhower says that “we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions,” that is “new to the American experience.” Necessity compels America to defend its interests and domestic order by using its affluence to expand military capability. In this respect, Eisenhower’s call for America to embrace what he calls in his First Inaugural Address “the responsibility of the free world’s leadership” is the realization of Hamilton’s (and Washington’s) expectation that America would one day rival Great Britain as a commercial Great Power.

Herbert Agar, a journalist and historian in the age of Eisenhower, sheds light on why Eisenhower feels it is necessary to make a case for American international leadership. Agar writes that “we were naïve about war, refusing to see it as ‘the most deadly form of politics’… we had long believed that the United States lived in a ‘safe’ corner of the world—too far away to share the immemorial fears of other nations.”[27] Eisenhower himself seems deeply concerned about the “tried-and-true” doctrine accepted by Robert Taft and the Republican Senate, that America can satisfy all its needs alone and therefore can continue to go its own way without concern for what happens in the rest of the world. Eisenhower is distinguished from his fellow Republicans as a man who “had seen the world and had no such illusions.”[28] Having led Americans during the conflict that forced America to admit the “necessity of Europe,” he sees it as his task to bring about a maturation of American foreign policy.[29] To be sure, Truman’s administration begins the process of maturation. However, Truman does not seem to grasp that the character of international relations does not mirror that of American domestic politics. Instead, he seems to believe that a quid pro quo approach to foreign policy can work because nations can always reach an agreement if they are willing to compromise.[30] The maturation of policy and strategy that does begin under Truman is therefore due largely to the efforts of others—especially, Acheson, Marshall, and Kennan. By the time that Eisenhower takes office, the United States still enjoys victory without a coherent intent.[31]

Eisenhower is convinced that “the United States cannot live alone.”[32] And if America must live with other nations, it would be best to maintain its postwar position of leadership it found itself in after the Second World War. Eisenhower presents the struggle for America’s way of life as no longer a domestic experiment but “a question that involves all humankind,” as he says in his First Inaugural Address. His Farewell Address describes America enmeshed in a global struggle against “a hostile ideology—global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method.” Such lines from Eisenhower’s Address seem to echo the rhetoric of Woodrow Wilson, whose Address Requesting a Declaration of War Against Germany appeals to “considerations of humanity and right” when calling for American involvement in the First World War.[33]

But unlike Wilson, Eisenhower self-consciously eschews the activist spirit of progressive democracy. He writes in a 1954 note to himself, “We are [so] proud of our guarantees of freedom in thought and speech and worship… that, unconsciously, we are guilty of one of the greatest errors that ignorance can make—we assume that our standard of values is shared by all other humans in the world.”[34] In private, Eisenhower critiques the Truman administration for overselling the gospel of American world leadership. He does not share even the limited hopes of his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who aspires to do more than just enforce the possibility of “liberal intercourse with all nations,” as Washington had put it.

Why then would Eisenhower make such lofty, even “Wilsonian,” appeals in his Farewell Address? John Lewis Gaddis indicates an avenue of interpretation that may reconcile the apparent discrepancy between Eisenhower’s public speech and private opinion. Eisenhower agrees with John Foster Dulles that “we are a product and a representative of the Judaic-Christian civilization,” and therefore, American foreign policy must express itself (on some level) as love of one’s neighbor. But when asked: “Who is my neighbor, and how do I love him?” Eisenhower typically answers in terms of economic necessity rather than moral idealism. Eisenhower and Dulles “could agree that the chief American interest in the world was access to the world, and that in turn required a world of at least minimal congeniality.”[35] Unlike Dulles, Eisenhower emphasizes the necessity of securing American free trade over the hope for effecting the conversion of Russia. In this respect, Eisenhower expresses a similar position to that of Washington: commercial interest is what drives American involvement in foreign affairs.

Still, Eisenhower also agrees with Washington that the president must convey the economic imperative of American foreign policy in moral terms that approximate the Christian duty of charity. In this sense, both presidents perceive that religion and morality are necessary supports for security and prosperity in the American regime: “honesty is always the best policy.” Eisenhower disavows democratic evangelism, yet he recognizes that American leadership in foreign affairs requires a moral (and pseudo-Christian) rationale. He sees that the president must be a moral leader to rally Americans for doing what is necessary to secure the national good. He therefore assumes a nearly “Wilsonian” rhetoric for “Hamiltonian” purposes. Tellingly, a month before his inauguration (at which he opens his address with “a little private prayer”), Eisenhower informs a group of reporters that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.”[36] Much like Washington, Eisenhower judges the stability of international relations by the freedom of merchants, not the success of progressive missionaries: “If you can’t make a living in the long run,” Eisenhower says in a 1953 press conference, “your people are ground down, and you have a new form of government.”[37] Eisenhower’s “New Look” strategy, which relies on nuclear deterrence to defend strongpoints of Western interest, exemplifies his calculating approach to foreign policy, characterized as it is by recognition of hard necessities rather than indulgence of soaring hopes.[38]

Eisenhower’s call for America to maintain its leadership abroad is a circumspect response to a novel situation in which extension of American influence would be necessary for securing America’s prosperity and way of life. Washington instructs America to avoid engagement in frequent controversies, “the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns.” But he also alludes to a time “not far off” when America might have to undertake new modes of securing the national good. Eisenhower recognizes this necessity and sets out to prepare a new line of defense for America consisting of both arms and allies.

Allies and the Military Industrial Complex

It remains to be seen how precisely Washington and Eisenhower’s foreign policy counsels agree on the use of military force and diplomacy. Both presidents advise mitigating the ill-effects of these necessary functions. But how does Eisenhower’s embrace of extensive diplomatic relations and augmented military capability reflect Washington’s principle that foreign policy should follow what Washington calls in his Farewell Address “the natural course of things”?

What seems to be the most obvious point of rupture between Washington and Eisenhower is their treatment of permanent alliances. While Washington throws his rhetorical weight against permanent political connections with foreign powers, Eisenhower attributes great value to alliance partnerships. In his Farewell Address, Eisenhower speaks of America’s responsibility to help the world become “a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect,” not “a community of dreadful fear and hate.” He evokes the image of a conference table at which even the weakest nations will come “with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength.” To bring about this community of peace and justice, Eisenhower states in his “Chance for Peace” speech that America and her “valued friends, the other free nations,” must stand united in defense of their way of life.

For Eisenhower, the alliance of free nations is not simply an ideal; it is a brute necessity. Eisenhower’s experience leading the Allies in Europe during World War II convinced him that multilateral cooperation would be necessary for containing the Soviet threat after the war.[39] America would need to view its own strategy as part of an international effort, and it would have to do this without relinquishing national independence. In a draft chapter for his presidential memoirs, Eisenhower elaborates on America’s need for allies and multilateral action:

United States defense policy is based upon membership in a system of alliances…. The reason for our dependence on these alliances is simple. With all its resources, the U.S. does not have the manpower to police every area of the world… Recognition of this fact constituted the essence of the “new look” which emphasized U.S. development of mobile air and sea power for use in our role in the collective defense of the world.[40]

The possibility of a realist isolationism ends with the Second World War.[41] America now requires diplomatic ties that reflect its new permanent interests abroad. Eisenhower concludes his Farewell Address with a prayer that, among other intentions, “that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities.” As discussed above, while Eisenhower presents these responsibilities as a duty to the international community, he understands them primarily in terms of America’s own national interest. The Soviet Union could invoke its unifying mission to spread communism worldwide; the United States would need to speak in terms of an alternative mission to unite the free nations against Soviet expansion.

While Washington argues that alliances will force America to become involved prematurely in European conflicts, Eisenhower sees that an immense European conflict has compelled America to assume leadership of a Great Power alliance to conserve American involvement overseas. This judgment is behind Eisenhower’s caution about American involvement in Southeast Asia. In a conversation reported by his National Security Adviser Robert Cutler, Eisenhower argues that “unilateral action by the United States in cases of this kind would destroy us. If we intervened alone in this case we would be expected to intervene alone in other parts of the world.”[42] Eisenhower uses allies to maintain a global grand strategy without overextending American resources or manpower. In this way, he adhered to the spirit of Washington’s counsel, even if not to the letter. “Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground?” is a question that Eisenhower echoes from Washington’s Farewell Address.

Eisenhower’s reliance on allies also reflects his Washingtonian unease about the ill-effects of an “overgrown” military on America’s domestic political order. The effective use of allies would enable America to limit its “military-industrial complex”—that most iconic phrase from Eisenhower’s address:

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions.

In keeping with Washington’s principle that military strength must follow circumspection about domestic and foreign necessities, Eisenhower acknowledges that a permanent military industry and a large defense “establishment” are not desirable in themselves but are now necessary to secure America’s safety and interests. “We recognize the need for this development,” Eisenhower said, “yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.” This is true even though the military-industrial complex poses a risk to “the counsels of government.”

Like the “military establishments” that Washington admonishes Americans to keep in check, the military-industrial complex risks American liberties—and the American regime. “Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.” Eisenhower’s observations closely reflect Tocqueville’s on the danger that a strong military poses for a democracy. As Tocqueville writes in Democracy in America,

War does not always give democratic peoples over to military government; but it cannot fail to increase immensely the prerogatives of civil government in these peoples; it almost inevitably centralizes the direction of all men and the employment of all things in its hands. If it does not lead one to despotism suddenly by violence, it leads to it mildly through habits.[43]

Remarkably, Tocqueville suggests the same remedy that Eisenhower advises: a professional military must be balanced by “enlightened, regulated, steadfast, and free citizens,” to use Tocqueville’s words—or, in Eisenhower’s, “an alert and knowledgeable citizenry.”[44] When a large military is necessary for a democracy, the democratic statesmen must encourage citizens to be cautious about the political influence of forces dedicated to security.

Raymond Aron helps to qualify this comparison of Tocqueville and Eisenhower’s thought when he writes that “the cold war to some extent created within the United States the modern equivalent of what Tocqueville considered inevitable in wartime… There was, however, one major difference in that arms’ manufacture rather than war itself became the great industry.”[45] That is, Eisenhower recognizes the economic as well as political danger posed by the military-industrial complex. Speaking to the American Society of Newspaper Editors on April 16, 1953, Eisenhower points out that “every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed…”[46] At times, Eisenhower’s speeches seem to call for disarmament as an ideal goal. Yet, his fundamental concern is that arms not become an end in themselves. Gaddis summarizes this view of military strength in Clausewitzian terms: “The major premise Eisenhower retained from reading the Prussian strategist was that in politics as well as in war, means had to be subordinated to ends; effort expended without purpose served no purpose, other than its own perpetuation.”[47] Both Washington and Eisenhower acknowledge the need for statesmen to prepare for war but not to let preparedness distract from that which one must defend. Si vis pacem para bellum aptly describes both presidents’ approaches to military capability. Yet both also sought to restrain America from unsheathing the sword unnecessarily.

Eisenhower recognizes the same danger that Washington observes about standing armies. But in keeping with Washington’s circumspection, Eisenhower acknowledges the necessity of a large military. Both presidents subordinate their generalship to statecraft, fully aware of the necessity and the political problem of a large military.[48] Both see that the president must not defend his country at the expense of his country’s way of life. The statesman, as Aristotle wrote, must ensure that his country can “live well,” not merely “live.”[49] Washington and Eisenhower embrace this responsibility, articulating for different times and circumstances distinct policies that rest on kindred assessments of the right relationship between domestic political order and foreign policy.

Duty and the National Interest: The Moral Underpinnings of American Foreign Policy

Washington and Eisenhower share more than just a common understanding of the pragmatic principles that should inform American foreign policy. They agree that a moral framework deriving from the character of the American regime must define how America acts abroad. Washington says that it is “the interest and duty of a wise people” to preserve the Union; Eisenhower praises those who serve the “national good.” These statesmen are circumspect about the international situation, but also about the moral character of America’s regime, built as it is on a doctrine of legitimacy that derives authority from the consent of the governed and the preservation of unalienable rights.

Hobbes and Locke claim that human beings have a right to everything necessary for self-preservation because, as Locke writes in the Second Treatise of Government, everyone “is bound to preserve himself.”[50] No one could blame someone in the state of nature—the state of nearly complete self-reliance—for doing whatever is necessary to survive. The social contract theorists conclude from this fact that human beings have a right to anything necessary for survival. The right to self-defense (that is, the right to life) is the fountain of all other rights, such as property rights. The American regime follows this logic: to an American, nothing is more unjust than the assault on another individual’s life or harmless private activity. “Don’t tread on me”—or on any of my neighbors. The ultimate justification for the use of force is self-preservation; the proximate justification is the protection of liberty and property, which are necessary for comfortable survival.[51] This blending of morality and utility necessarily informs how Americans view foreign policy. For Washington as much as for Eisenhower, America must act for the sake of its own rights and interest, whether one presents this interest in terms of the “Union” or service to the “national good.” Americans will admire other nations that seek freedom and independence but must balance this admiration with prudent circumspection, as the Declaration itself sets out.[52]

Washington and Eisenhower would agree with John Quincy Adams that America must be the champion and vindicator of her own.[53] The fundamental national interest is national independence: America must be free from “foreign intrigue” and “foreign influence” (Washington’s phrases) if it is to maintain its way of life as “a free and religious people” (Eisenhower’s). Consequently, American foreign policy must be self-interested but also must uphold the justice of securing one’s own rights. The president must uphold the morality of the proposition that “we have a right to act as our circumstances and our interest require,” as Henry Clay (later John Quincy’s Secretary of State) articulated in an 1818 speech to the House of Representatives.[54]

Washington instructs Americans to maintain the Constitution and the Union “sacredly” because national union is both an object of devotion and the prerequisite for “collective and individual happiness.” Accordingly, American foreign policy must prioritize defense of the Union while also securing the possibility for individuals to pursue material prosperity through foreign commerce. Eisenhower promotes the same ends when he says that defending America’s free government is a “noble” purpose that requires “readiness to sacrifice.” When Eisenhower preaches “our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice,” he is not simply invoking cosmopolitanism. Rather, he is appealing to the pride and honor of a “Nation” (Eisenhower capitalizes this word only when it refers to America) that hopes to accomplish great things, both for itself and for humanity.[55] In a similar way, Washington invites Americans to associate the national interest with honor and virtue. In his Farewell Address he asks (rhetorically): “Can it be that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a nation with its virtue?” The insoluble paradox of American foreign policy is that virtue must be pursued because it is the best policy; virtue and honor enable “liberal intercourse with all nations” in a way that is supposed to reflect humanity, pride, and interest all at once.

This morality of American foreign policy may not be completely coherent, but it is a necessary corollary to the American regime. It is a credit to the circumspection of both Washington and Eisenhower that they admit this fact of American political life into their foreign policy counsels. In their respective Farewell Address, they speak to a deeply felt (and deeply American) hope for a world in which the noble are honored for their worthiness and beneficence. These statesmen perceive that the concern for honor and virtue leads one to take up duties one otherwise would not embrace, but which may be necessary for the national interest. Admittedly, the love of honor uneasily accompanies the selfish concern for one’s own good. But in the national moral life that underpins American foreign policy, honor and self-interest are stronger motivators than calculations of long-term necessity.[56] In order to act as our circumstances and interest require, Americans require a political morality of international action that is clearly rooted in the national interest and in a spirited appeal to the dignity of our American way.

Washington, Eisenhower, and the Enduring Necessity of Circumspect Foreign Policy

Washington and Eisenhower’s Farewell Addresses indicate a shared conviction that the president must make prudent use of the means available to secure American interests. At every opportunity, Washington qualifies his warnings, stating that America must avoid overgrown military establishments, permanent alliances, and artificial ties. Eisenhower fulfills Washington’s principles, modifying them in practice according to changed circumstances. Washington urges America to make foreign policy serve the national interest, and Eisenhower recognizes that an active foreign policy is the best way to fulfill this mandate—however much America’s “new look” requires a shrewd use of alliances to prevent overextension, as well as an active citizenry to preserve the American regime.

These statesmen grasp the nature of international politics and the character of the American democratic republic. Knowledge of the American regime leads them to articulate their foreign policy counsels in connection with moral appeals to sacred rights and honor. In this way, they show the need for circumspection at home and abroad. The exigencies of one’s regime and of the current international situation determine the means suitable for securing the end. Eisenhower does not adhere to the letter of Washington’s Farewell Address, but he and Washington alike follow the principles of prudent statecraft, accounting for particulars while pursuing the enduring goal of America’s national good.

Michael R. Gonzalez is a Postdoctoral Research Associate with the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University. He studies the intersection of IR theory and the history of American foreign policy, as well as the conflict between classical Christian and early modern political philosophy. He received his doctorate in political science from Baylor University after undergraduate studies at the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

NOTES

[1] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, bk. 6.7. See also, Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, Q 49, Art. 7, resp. Cf. ST Q. 47, Art. 2, resp.

[2] Washington, “Farewell Address” (September 19, 1796).

[3] Mead, Special Providence, 45–46. Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2002, I.2.5, 217–20. Cf. Lord, The Modern Prince, 2018, 153–59.

[4] Mead, Special Providence, 58. See, for example, Tansill, “Correspondence: The Case for American Isolation.”

[5] Mead, Special Providence, 59. On p. 130, Mead describes how adherents to the Hamiltonian tradition of American foreign policy were able to accept American reliance on alliances because “they had always taken Washington’s Farewell Address as pragmatic counsel rather than holy writ.”

[6] Felix Gilbert argues that correspondence between the Farewell Address and Federalist No. 11 make “it almost certain that Hamilton had [the Federalist] not only on his bookshelf—as would have been a matter of course—but also on his writing desk when he drafted the Farewell Address.” Gilbert, To the Farewell Address, 1970, 132–33.

[7] Hamilton, The Federalist No. 11, 51.

[8] Ibid, 55.

[9] “It became an expression of a national point of view about ourselves and our place in the world, a view which contrasted the simple virtues of our Republic with the subtle and complex qualities (some said corruptions) of Europe.” Fromkin, “Entangling Alliances,” 688.

[10] It is worth noting that Washington’s dictum “honesty is always the best policy,” which follows shortly after the quoted passage, is an element of the Address that is distinctly from Washington. It appears in the first draft (sent to Hamilton on May 15, 1796) but does not occur in Hamilton’s abstract for the speech. It also is absent from Hamilton’s major draft. Yet the phrase occurs again in Washington’s final manuscript, implying that it had been a maxim Washington personally held to be true. For the manuscripts mentioned, see the Appendices in Gilbert, To the Farewell Address.

[11] Gilbert, To the Farewell Address, 1970, 48.

[12] Consider Palmerstone’s view on treaties, as expressed to Talleyrand: “We have no objection to treaties for specific and definite and immediate objects, but we do not much fancy treaties which are formed in contemplation of indefinite and indistinctly foreseen cases. We like to be free to judge of each occasion as it arises, and with all its concomitant circumstances and not to be bound by engagements contracted in ignorance of the particular character of events to which they are to apply.” Cited in Fromkin, “Entangling Alliances,” 689. Cf. Gilbert, 122: “In his draft for the valedictory [i.e. the speech that became the Farewell Address], Washington elaborated on the dangers of foreign interference in American politics and on the necessity of realizing that in foreign affairs, each nation is guided exclusively by egoistic motives.”

[13] The immediate occasion of Seward’s address in 1853 was Russia’s armed suppression of Hungarian independence. Seward ends his speech with a call for the Senate to ratify a statement of protest against Russia and sympathy for Hungary. C.f. Henry Clay’s observations in Bartlett, The Record of American Diplomacy, 286. Unlike Clay, Seward advocates greater American involvement in foreign affairs.

[14] Seward, “Washington’s ‘Entangling Alliances,’” 103.

[15] Usher, “Washington and Entangling Alliances,” 37.

[16] Usher, 37–38.

[17] Cf. The Federalist No. 10.

[18] Storing and Dry, The Anti-Federalist, 152. The Continental Congress’s Declaration of Rights (adopted on October 14, 1774) also expresses this sentiment (Christopher A. Preble, Peace, War, and Liberty [Washington, D.C: Cato Institute, 2019], 18).

[19] Consider especially Patrick Henry’s view. Storing and Dry, The Anti-Federalist, 303.

[20] Washington, “First annual Message to Congress” (January 8, 1790).

[21] George Washington, “Eighth Annual Message to Congress” (December 7, 1796). Cf. Hamilton, Federalist No. 11: “There can be no doubt, that the continuance of the union, under an efficient government, would put it in our power, at a period not very distant, to create a navy, which, if it could not vie with those of the great maritime powers, would at least be of respectable weight, if thrown into the scale of either of two contending parties…” and No. 24: “If we mean to be a commercial people, or even to be secure on our Atlantic side, we must endeavour, as soon as possible, to have a navy.”

[22] “A small naval force then is sufficient for us, and a small one is necessary. What this should be, I will not undertake to say. I will only say, it should by no means be so great as we are able to make it” (Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query 22).

[23] Gilbert, To the Farewell Address, 122-123, 139.

[24] Emphasis added. “Washington’s First Draft for an Address,” in Gilbert, 139.

[25] Eisenhower, “Farewell Address” (January 17, 1961).

[26] Eisenhower, “First Inaugural Address” (January 20, 1953).

[27] Herbert Agar, The Price of Power, 4-5.

[28] Agar, The Price of Power, 168. Regarding the tradition that Taft represents, cf. John Randolph’s Speech on the Greek Cause (January 24, 1824), in which Randolph uses Washington’s Farewell address to argue for “a fireside policy; for, as has truly been said, as long as all is right at the fireside, there cannot be much wrong elsewhere….” Reproduced in Kirk, John Randolph of Roanoke, 403 (Appendix II).

[29] Agar, 169.

[30] John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 15–16.

[31] Agar, The Price of Power, 4.

[32] Eisenhower, The White House Years: Mandate for Change (1953-1956), 214.

[33] Wilson, “Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War Against Germany” (April 2, 1917).

[34] Quoted in Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 128.

[35] Gaddis, 130.

[36] Eisenhower’s remark was not precisely recorded, but this quotation seems to be the most likely approximation. For a thorough record of the attempts to reconstruct what Eisenhower said, see Patrick Henry, “‘And I Don’t Care What It Is’: The Tradition-History of a Civil Religion Proof-Text,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion: 35–49.

[37] Quoted in Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 132.

[38] See John P Burke and Fred Greenstein, How Presidents Test Reality, 108. Gaddis does not seem correct in suggesting that Eisenhower was preoccupied with fiscal conservatism for its own sake, though Gaddis acknowledges that Eisenhower’s concerns with fitting means to ends is ultimately Clausewitzian. See Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 133.

[39] Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, 459. “During the war it was demonstrated that international unity of purpose and execution could be attained, without jeopardy to any nation’s independence, if all were willing to pool a portion of their authority in a single headquarters with power to enforce their decisions.”

[40] Cited in Burke and Greenstein, How Presidents Test Reality, 108.

[41] Agar, The Price of Power, 17.

[42] Burke et al., How Presidents Test Reality, 104.

[43] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, (vol. II, pt. 3, ch. 22) 621.

[44] Tocqueville, (vol. II, pt. 3, ch. 22) 622.

[45] Aron, The Imperial Republic, 49–50.

[46] Cited in Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 131.

[47] Gaddis, 133. Agar argues that part of America’s naivety up until Eisenhower’s presidency was a failure to see war as “the most deadly form of politics” and to accept the political consequences of military victory. Agar, The Price of Power, 4.

[48] “The good politician, Aristotle tells us, is someone capable of ‘architectonic and practical thinking.’ He ‘uses’ arts or kinds of expertise such as generalship and rhetoric but subordinates them to the overall good it is his job to pursue.” Lord, The Modern Prince, 2018, 26, 28.

[49] Aristotle, Politics, 1280b5-1281a10.

[50] Locke, Two Treatises of Government, ch. 2, sec. 6.

[51] Cf. Tarcov, “Principle and Prudence in Foreign Policy,” 49–50. See also West, The Political Theory of the American Founding, 141, 143–45.

[52] “Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes….” The Declaration of Independence, in Jefferson, Selected Writings, 8.

[53] John Quincy Adams, “Speech to the U.S. House of Representatives on Foreign Policy” (July 4, 1821).

[54] Cited in Tarcov, “Principle and Prudence in Foreign Policy,” 59.

[55] It was Eisenhower who, on July 30, 1956, signed into law the bill making “In God We Trust” the national motto and adding Lincoln’s phrase “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance.

[56] See Cropsey, “The Moral Basis of International Action,” 89–90.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, John Quincy. “Speech to the U.S. House of Representatives on Foreign Policy, July 4, 1821.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center, n.d. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/july-4-1821-speech-us-house-representatives-foreign-policy.

Agar, Herbert. The Price of Power. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1957.

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologiae. Translated by Laurence Shapcote. Latin/English Edition of the Works of St. Thomas Aquinas. Lander, WY: The Aquinas Institute for the Study of Sacred Doctrine, 2018. https://aquinas.cc/la/en/~ST.I.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Robert C. Bartlett and Susan D. Collins. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

———. Politics. Translated by Carnes Lord. Second edition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Aron, Raymond. The Imperial Republic. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1974.

Bartlett, Ruhl J., ed. The Record of American Diplomacy. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1954.

Burke, John P., Fred I. Greenstein, Larry Berman, and Richard H. Immerman. How Presidents Test Reality. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 1991.

Cropsey, Joseph. “The Moral Basis of International Action.” In America Armed: Essays on United States Military Policy, edited by Robert E. Goldwin, 71–91. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 1963.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe. The Great Commanders. New York, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1976.

———. “Farewell Address.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center, n.d. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-17-1961-farewell-address.

———. “First Inaugural Address.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center, n.d. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-20-1953-first-inaugural-address.

———. The White House Years: Mandate for Change (1953-1956). Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1963.

Fromkin, David. “Entangling Alliances.” Foreign Affairs 48, no. 4 (July 1970): 688–700.

Gaddis, John Lewis. Strategies of Containment. Rev. and Expanded ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Gilbert, Felix. To the Farewell Address. Princeton Paperbacks. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1970.

Hamilton, Alexander, John Jay, and James Madison. The Federalist. Edited by George W. Carey and James McClellan. The Gideon Edition. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2001.

Henry, Patrick. “‘And I Don’t Care What It Is’: The Tradition-History of a Civil Religion Proof-Text.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 49, no. 1 (March 1981): 35–49.

Jefferson, Thomas. Selected Writings. Edited by Harvey C Mansfield. Crofts Classics. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1996.

Kirk, Russell. John Randolph of Roanoke: A Study in American Politics, with Selected Speeches and Letters. Fourth Edition. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1997.

Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. Edited by Lee Ward. Indianapolis, IN: Focus, 2016.

Lord, Carnes. The Modern Prince. Second American edition. New York, NY: Encounter Books, 2018.

Mead, Walter Russell. Special Providence. A Century Foundation Book. New York, NY: Routledge, 2009.

Preble, Christopher A. Peace, War, and Liberty. Washington, D.C: Cato Institute, 2019.

Seward, W. H. “Washington’s ‘Entangling Alliances.’” The American Advocate of Peace and Arbitration 53, no. 4 (May 1891): 102–3.

Storing, Herbert J., and Murray Dry, eds. The Anti-Federalist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Tansill, Charles Callan. “Correspondence: The Case for American Isolation.” Thought XV, no. 58 (September 1940): 492–94.

Tarcov, Nathan. “Principle and Prudence in Foreign Policy: The Founders’ Perspective.” The Public Interest, America’s Defense Dilemmas: II, 76, no. 76 (Summer 1984): 45–60.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. Translated by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Usher, Roland G. “Washington and Entangling Alliances.” The North American Review 204, no. 728 (July 1916).

Washington, George. “Eighth Annual Message to Congress.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center, n.d. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches.

———. “Farewell Address.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/september-19-1796-farewell-address.

West, Thomas G. The Political Theory of the American Founding: Natural Rights, Public Policy, and the Moral Conditions of Freedom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Wilson, Woodrow. “Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War Against Germany.” University of Virginia: The Miller Center, September 9, 2020. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/april-2-1917-address-congress-requesting-declaration-war.